Carvana is the fastest growing used car dealer in the US while also having the industry’s best margins. That rare combination comes from having more vertical integration and scale advantages than any of their competitors. Traditional used car dealers have more local, outsourced, and variable expense business models.

Historically, the used car market has been extremely fragmented because no competitors benefit from economies of scale—especially on a national level. Today, CarMax is the industry leader, and they only have around 2% of the market. I think Carvana can change this market share dynamic though.

To grow, a traditional used car dealer has to open a new brick and mortar location, hire employees and commission-based salespeople, and stock the lot with a few hundred cars. Used car dealers sell locally so they advertise locally to generate foot traffic, and their technology is minimal and/or outsourced to third parties.

Dealers selling cars via commission-based salespeople is important for two reasons. One, that commission is a variable expense the dealership has to pay on every car sold. Carvana does not have that variable expense. And two, commission-based salespeople are incentivized to sell cars for as much money as they can get. First and foremost, that sucks for the customer. But it also increases the value of the car loan, which leads to higher default rates on those loans. Financing is an important part of Carvana’s advantage that I’ll dive deeper into later on.

Most used car dealers do not have many expenses that can be shared among different locations, so their economies of scale are minimal. Three locations for a used car dealership are going to be roughly 3x as profitable as one location. On the other hand, Carvana’s profitability is going to scale faster than their volume due to their fixed cost business model.

Carvana does not have physical used car dealerships. They buy cars from various sources, process and recondition them at their inspection centers strategically placed around the country, and then list the reconditioned cars on their website that anyone around the country can purchase from. Carvana’s own logistics network moves cars around as needed and delivers them to customers. And they do their own financing, which is a critical but often outsourced part of a used car transaction. Finally, all of this logistics and their consumer website are tied together on their custom software platform that is built and managed in-house.

“We have developed proprietary logistics software and an in-house nationwide delivery network which is aimed at allowing us to predictably and efficiently transport cars while providing customers with a distinctive fulfillment experience. Our logistics network and technologies that support it are based on a ‘hub and spoke’ model, which connects Reconditioning Sites to vending machines and hubs via our fleet of multi-car and single-car haulers. This allows us to efficiently manage locations, routes, route capacities, trucks, and drivers while also dynamically optimizing for speed and cost. This proprietary logistics infrastructure enables us to offer our customers and operations team highly accurate predictions of vehicle availability, to minimize delays, and promote a seamless and reliable customer experience.” – Carvana 2024 10-K

As the spokes of this hub-and-spokes logistics model split off and expand into more areas of the country, Carvana gets closer to its customers. Rural customers can get more cars delivered in a few days. Urban customers can get more cars delivered next day. Quicker delivery times are a better customer experience that increases conversion rates and sales.

As sales increase, Carvana has more money to invest in logistics, advertising, and inventory. Carvana’s centralized inventory that can be sold to any customer across the country is a significant advantage. Most used car dealers have a few hundred cars on their local lot, and even dealers with many locations do not have the logistics infrastructure that Carvana has that regularly moves cars across the country. Carvana’s broad selection of inventory leads to higher conversion rates and more sales.

As these logistics flywheels result in more cars sold, Carvana’s billions of dollars of fixed costs get leveraged over more sales. As the fixed cost per unit decreases and Carvana’s incremental variable expenses to sell a car are low, Carvana can price off that lower incremental cost. Lower prices mean more sales and more cars to push through their already built-out infrastructure, which covers their fixed costs even more and further lowers the fixed cost per vehicle sold. Lower prices also result in lower loan-to-value ratios on their loans, which benefits the financing part of their business via lower default rates.

Another benefit of Carvana’s nationwide infrastructure and website is that they naturally benefit from vehicle cost arbitrage across geographies. Competitors buy and sell locally to minimize logistics, and because they usually don’t have customers all around the country. Carvana buys and sells nationally, so they will naturally buy more cars where the supply is highest relative to demand (paying lower prices) and sell where demand is highest relative to supply (getting higher prices).

“Our business benefits from powerful network effects. Our logistics capabilities allow us to offer every car in our inventory to customers across all of our markets. As we add markets, we expect to increase overall demand, which would enable us to carry a larger inventory. A broader vehicle inventory would further improve our offering across our markets, enabling us to increase market share. Furthermore, we anticipate that increased brand awareness, driven by national advertising, will allow us to expand our national inventory and further these network effects.” – Carvana 2022 10-K

Underwriting loans is generally not the core competency of used car dealers, so they outsource financing to third-party lenders. This makes sense as financing and selling cars are two very different skill sets that one company culture is usually not conducive with, but this dynamic creates misaligned incentives.

Buying a used car at a traditional dealer is a confusing negotiation with multiple parts. And the salesperson will often adjust different parts of the deal (sticker price, trade-in value, vehicle service contract, etc) to make their margin and commission. Moving money around among various buckets means the third-party lender struggles to know the true value of the car.

A traditional dealer also does not care about the performance of those loans because they get paid a fee to generate leads for third-party lenders no matter what. The commission-based salesperson just wants to sell the car for as much as possible, which is bad for default rates and loan performance.

Alternatively, Carvana is both the dealer and lender and has very aligned incentives. They have all the information so they can underwrite better than third parties can (as proven by their subprime loans outperforming the rest of the industry). This also means there are no third party or dealer markups on the loan. This is a perfect example of a vertically integrated business cutting out third party fees and markups to generate better prices for the end user.

These better prices result in lower defaults, better loan performance, and more profits that Carvana invests back into logistics, inventory, and advertising, benefiting all of these flywheels.

Carvana’s scaled reconditioning business also benefits their financing segment. Carvana has a standardized 150-point inspection process that they go through for every car that gets sold on their website. This results in higher quality cars on average than their competitors, which means their cars should break down less often and thus customers will default on their loans less often.

So, if keeping financing in-house and managing their own logistics is so beneficial, why haven’t Carvana’s competitors done it? Won’t CarMax and others copy Carvana now that the benefits are obvious?

In short, vertical integration is easier said than done. Most company cultures are built to be good at one or two things—for example, building logistics or software or financing or retail vs wholesale or B2B vs B2C. It is orders of magnitude easier to be good at one or two of those things than it is to be good at all of them. Used car dealers generally try to be good at B2C retail sales. Carvana does all of them—and by some stroke of genius and luck, they seem to be good at them all. Every other company of meaningful size that has tried to vertically integrate the used car industry has failed. I believe one of the main reasons Carvana didn’t fail—despite coming oh so close!—is how they were founded and their relationship with DriveTime.

DriveTime is a used car dealer that specializes in offering subprime financing to customers with bad credit. DriveTime was founded in 2002 by Ernest Garcia II, the father of Carvana’s founder Ernie Garcia III. Ernie originally founded Carvana inside DriveTime in 2012 and then spun it off in 2014. Carvana has benefitted immensely from this relationship with DriveTime.

In its early years, Carvana was able to save many tens of millions of dollars by leveraging DriveTime’s reconditioning centers and not having to build their own. The high fixed cost of building reconditioning centers is a significant barrier to entry that other Carvana competitors have struggled with. Even more than just the cost, Carvana learned how to recondition cars from a company that had been doing it for years.

From DriveTime, Carvana also learned how to underwrite subprime loans, which remains a critical part of their competitive advantage today. Most used car dealers—like CarMax—are not financing experts, especially for subprime customers, so they outsource this to a third-party who takes a cut. On average, Carvana earns over $2,000 of gross profit per car from underwriting loans themselves.

Moving on, I believe the most underappreciated competitive advantage Carvana has is their ability to buy cars at scale from their own customers. You can go to Carvana’s website, enter your car’s VIN and a few details, get an offer to buy it in 5-minutes, and Carvana will pick it up from your home within the next couple of days. This customer experience for selling a car is orders of magnitude better than the time-consuming in-person negotiations involved in driving to used car dealers and getting offers from them.

After picking up the car, Carvana reconditions it and retails the ones they deem fit for their website, and they wholesale the rest. Importantly, Carvana also owns the second largest used car wholesale business in the US, ADESA. Running the second largest wholesaler in the industry means Carvana has the best all-around data and pricing for retail and wholesale of used cars. This should allow them to buy customer cars better on average due to their always up-to-date knowledge of what cars are selling for on their website or at their wholesaler. And because they own ADESA, Carvana does not have to pay fees when selling cars wholesale—another benefit of vertical integration. Once again, this should add to Carvana’s ability to price cars lower than their competitors.

Carvana currently buys over 80% of their inventory from their own customers. This is a significant advantage for several reasons. The other way to buy used cars at scale is through wholesale auctions, but that is a competitive bidding process that incurs auction fees, which results in higher prices.

Sourcing inventory from their own customers is also a major benefit to Carvana’s infrastructure thanks to reverse logistics. Normal logistics delivers a product from a company to a customer. Reverse logistics goes from a customer to a company, generally when a product is returned. Buying hundreds of thousands of cars each year from their own customers means Carvana’s logistics infrastructure as a whole can be more efficient.

A significant cost to any logistics company is deadhead trips. This is when a truck is driving empty without freight, and it often happens after a customer delivery when the truck is returning to the company’s location. But because Carvana buys so many cars from customers and their entire buying, selling, and logistics infrastructure is integrated in the same software platform, Carvana can optimize routes so that their trucks drop off one car to a customer and then pick up a car from another customer before returning to Carvana with that new inventory. Deadhead routes are minimized and Carvana’s logistics is more efficient. This spreads more activity over their fixed logistics infrastructure, lowers fixed cost per unit, and feeds back into their flywheel of lower prices leading to more sales.

Sourcing inventory from their own customers at scale like Carvana does is a significant competitive advantage that would be very difficult for their competitors or for new startups to replicate. One, it requires a front-end retail website that is integrated on the backend with logistics and inventory.

Two, there are no other ADESAs to acquire to fully vertically integrate and benefit from the knowledge and lower pricing on the wholesale side. Used car wholesaling is much more concentrated than retail, and the top wholesalers are already owned by strategic third parties. It would be almost impossible for this part of Carvana’s moat to be replicated.

Finally, Carvana has a scaled reconditioning business, which allows Carvana to know the cost of fixing cars and to do it without paying a third-party markup. As described above, reconditioning is expensive, difficult to learn, and has already proven to be a barrier to entry for others trying to replicate Carvana’s business.

Carvana’s scale throughout their entire business also allows them to be a large advertiser across the country. Remember, most of their competitors are small and local, so they buy local advertising to drive foot traffic to their store. Carvana’s economies of scale in buying nationwide advertising gives them bulk discounts and lower prices per lead. Carvana’s vertically integrated, fixed cost business that benefits from economies of scale and network effects has given them the scale to benefit from this advertising advantage.

National advertising has helped Carvana grow to have the most brand awareness in the industry—despite still being smaller than CarMax (for now). Even more than brand awareness, Carvana has a cognitive monopoly for online used car buying and selling. A cognitive monopoly is when a single company or product or idea dominates public perception of that segment. When the general public thinks of online search, they think of Google. Most people say Kleenex instead of tissue—even if talking about another brand. Those are cognitive monopolies. Likewise, if you ask people about where they can buy or sell a car online, they say Carvana.

Very few companies ever benefit from becoming a cognitive monopoly, but it is a massive advantage when it does happen. Once the general public views a company or product as the default option for one specific market, it takes many years for that societal belief to go away.

As described throughout this post, Carvana’s scale benefits their business in many ways that ultimately result in lower prices, more selection, and a better user experience. On top of that, Carvana has become the default option for buying and selling used cars online, meaning many consumers will use Carvana without even considering their competitors. That is a very large barrier for others to overcome.

Over the past two years, Carvana has made many improvements to their business to cut expenses and grow more efficiently. The result of those fundamental gains has been unit growth reaccelerating to +33% in 2024 and +41% in Q2 2025 while adjusted EBITDA margins increased from -7.7% in 2022 to +12.4% in Q2 2025. To date, most of their operational improvements have gone to improving margins and becoming consistently profitable. Despite that, Carvana still sells comparable cars for $500 to $1,000 less than their competitors due to the many scale benefits of their fixed cost, vertically integrated business model. This price advantage is about to improve even more though.

Carvana’s long-term stated financial model is to earn an adjusted EBITDA margin of around 13.5%. Now that they are within striking distance of that level of profitability, they gave more clarity on the Q1 2025 conference call about what happens next. The answer was clear: scaled economies shared.

Scaled economies shared is an approach to business where the company passes on its benefits of scale to its customers in the form of lower prices. This is a very strong competitive advantage that is both rare and hard to compete with for two reasons.

First, most companies are not run by owner-operators and do not have a true long-term culture. So, for a hired CEO who was gifted stock and does not have long-term job security, their incentive is to increase the short-term profitability of the company, i.e., keep most profits for themselves instead of passing them along to customers in the form of savings. Second, most companies simply do not benefit from economies of scale enough to share any meaningful benefits of scale with their customers even if they wanted to.

Costco is the classic example of a scaled economies shared business. Their business benefits from scale in numerous ways, but no matter what, they keep their markups at 14-15% and their gross margins remain a little below that. For decades, Costco’s gross margin has remained 12-13% while their benefits of scale have been passed on to their customers. This is very difficult to compete with, and it is what Carvana is about to embark on.

“more mature markets with larger market shares are a couple of hundred dollars better than our average. And we still think that there’s very significant fundamental gains to be had. And I think when you start doing the math on that, it gets you well beyond our 13.5% target… we’re likely to take those fundamental gains and seek to share the significant majority of them with our customers to further separate our offering over time” – Ernie Garcia III, Q1 2025 earnings call

Given all the advantages and positive flywheels I have described in this post, I believe Carvana’s economies of scale and network effects have reached escape velocity. Their business is rapidly scaling and becoming more profitable, and they are about to share most of those improvements with their customers via lower pricing. As described, lower prices benefits their entire business in many ways. And this is relative to competitors whose commission-based salespeople and finance managers are all incentivized to charge car buyers as much as they can get away with.

Between Carvana’s massive scale advantages and the innovator’s dilemma, I don’t know how any of their current competitors could realistically challenge Carvana. To recreate Carvana’s advantages, CarMax would require years of self-funding billions of dollars of investments, but they would still be doing it at a disadvantage due to their existing physical store footprint with expensive real estate and salespeople. Disrupting your own business is hard, and changing a company culture is rare. As a non-founder led public company with shareholders who like their GAAP profits, I don’t know how CarMax can realistically change enough to be more competitive with Carvana. But even if CarMax surprises me, this is a very fragmented industry, and their other competitors are in even worse positions than CarMax.

Retailers generally compete on price, selection, service, and convenience. Carvana is a rare retailer who wins on all four; most have to make tradeoffs and compromises. Carvana is already $500 to $1,000 cheaper than their competitors on comparable cars, and I believe this will increase over time thanks to scaled economies shared. Carvana has tens of thousands of cars that can be delivered to your door compared to local car lots that have a few hundred cars.

Carvana has a pressure-free buying and selling experience that is quick and all online with transparent pricing and a 150-point inspection that gives consistently high-quality cars. You don’t have to deal with the scummy used car salesmen stereotype, you only have to enter your loan application details once and can search by monthly price, you don’t have to spend hours driving around to different dealerships, and on and on.

The service and convenience benefits that Carvana has basically entail every part of the car buying and selling experience. In a normal used car dealer, the customer could have a good experience with the physical dealer but still have a negative overall experience due to a third party reconditioner, lender, or logistics company. On the other hand, Carvana is vertically integrated and controls all critical operations of their business, so they can deliver a consistently great customer experience.

All companies eventually die, but I don’t know how anyone hurts Carvana’s business anytime soon. This is a physical business that moves 4,000-pound hunks of metal around. No amount of software or AI can get around the fact that facilitating the buying and selling of used cars requires a lot of land to store cars, inspection and recondition centers all around the country, and a fleet of trucks and haulers to move the cars around.

The cost and time to buy land and build physical infrastructure does not decrease like it does with building software. Building out a nationwide logistics network to compete with Carvana would probably take the next company about as long as it did Carvana (10 years). But if a competitor did have a unique differentiator, Carvana would see the threat coming and would have years to respond. And thanks to Carvana being founder-led and to Ernie’s nature, I believe they would be much less susceptible to the innovator’s dilemma.

But realistically, I don’t see them being disrupted anytime soon. This business is just incredibly hard in a way that few others are. It is not a coincidence that Carvana’s top two direct competitors, Vroom and Shift, both failed, and Carvana is literally the first public company in history to survive a -99% stock swing. Carvana’s unique founding within DriveTime was a massive benefit to use their reconditioning centers early on and to learn how to do financing.

If a new entrant can get around that barrier to entry, Carvana has spent $10 billion dollars over ten years to build out a nationwide logistics infrastructure, and that physical buildout cannot be bypassed. Carvana also owns the #2 B2B wholesaler, which might be impossible to replicate.

While doing all of that, the new entrant has to compete with a vertically integrated, scaled competitor who is actively trying to push down their prices while having a cognitive monopoly on the industry. And that competitor has a tier 1 founder/CEO and a company culture that executed one of the greatest comebacks in public company history. Good luck.

Selling used cars is a very fragmented industry and some consumers will always want to look at cars in person or buy and sell peer-to-peer, but I don’t see how any current or new competitor will stop Carvana from taking 10-20% market share. Their moat is too wide, they have the best customer experience, and the incentives are all in their favor. Carvana is actively trying to improve their business to lower prices, which benefits everything they do, while competitors have minimal economies of scale, are subject to the innovator’s dilemma, and have employees and company cultures that are incentivized to charge high prices and give worse customer experiences.

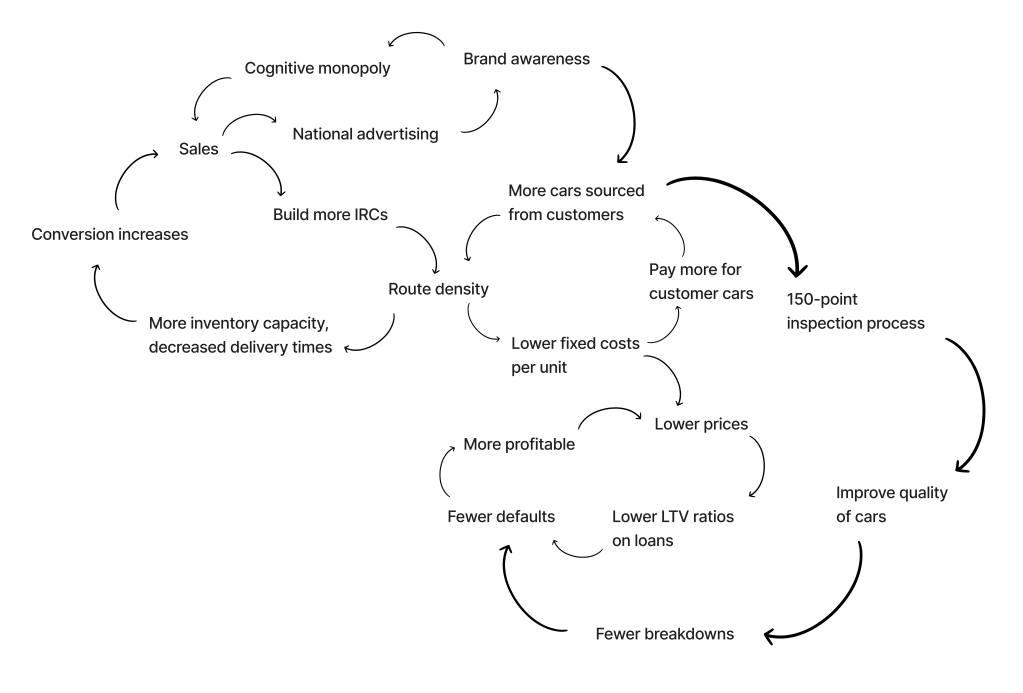

Below is my attempt to visualize Carvana’s numerous flywheels and how they interact and reinforce each other.